New Jersey’s urban growth pressure is likely to make it the first state in the nation where all of the land available for development is built out. The Garden State will not yet be built out by 2021, but there will be more acres of housing developments, shopping centers and industrial warehouses, and consequently fewer acres of farmland, forests and wetlands, than today.

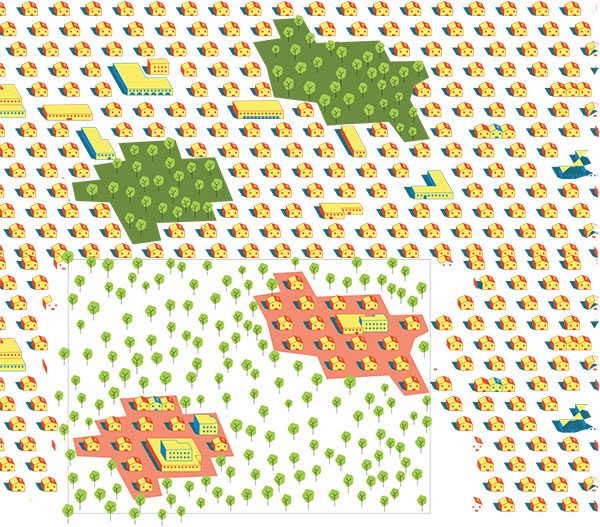

There is no doubt that New Jersey’s landscape will change in the coming years. The question is where, how much and at what socioeconomic and environmental cost? We present two scenarios for land use in the Garden State over the next decade. The two scenarios assume a moderately strong recovery but represent bookends for a range of possible outcomes shaped by different land-use policy visions.

Scenario One: Status Quo

The first scenario is a land-development pattern that follows the policies and trends of the past several decades. A recent study conducted jointly by our research centers at Rowan and Rutgers utilized land use data derived from high-precision aerial photography produced by the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection. The study revealed that, from 1986 to 2007, development patterns became faster and more dispersed in spite of a drop in population growth. The rate of development reached 16,169 acres per year and came at the annual expense of 8,490 acres of forest loss, 5,730 acres of farmland loss and 1,755 acres of wetlands loss.

However, it’s not only the magnitude of acres developed and open-space lost that is important. Equally, if not more, striking are the location and pattern of development and the subsequent socioeconomic/environmental impact. During the period covered in the Rowan-Rutgers study, housing spread into rural areas and consumed more acres of land per household than at any time in New Jersey’s history. By 2007, developed land had reached 30 percent of the state’s total territory, surpassing forested land to become the most prominent land-use type in the state. In other words, there are now more acres of subdivisions and shopping centers than there are of upland forests—which are forested areas exclusive of wetland forests.

This pattern of low-density development leapfrogging into sensitive rural areas is fragmenting forests, farmlands and wildlife habitat in a manner that degrades the viability of these important land functions, requires more vehicle miles to be driven and creates more social segregation—since the vast majority of rural sprawl is not affordable to most. Ironically, the rate of land development increased despite decreasing population growth. The increase in acres developed between 2002 and 2007 grew 4½ times faster than the increase in the state’s population during the same period. A significant amount of land converted from open space to development land was not based on demand to house a growing population but was the consequence of people relocating from older housing stock to new subdivisions in the rural fringe. Nearly half of the acres developed from 2002 to 2007 did not occur in the smart growth (urban/walkable) areas identified by the state.

If the land-use trends documented over the past two decades are projected into the next decade, we can expect that urban land will grow by about 150,000 acres (234 square miles), with a corresponding loss of 150,000 acres of farmland, forest and wetlands. More significantly, wildlife habitats will be reduced and the corridors that connect them will be fewer. More housing will be dispersed throughout the state’s environmentally sensitive rural areas. Because of this dispersed pattern, more expense will be incurred for police and rescue, trash pickup and school busing. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions, as well as maintaining our existing transportation infrastructure, will become more difficult as more vehicle miles are driven and additional roads built. At current trends we will increase impervious surface in the coming decade by 42,700 acres (67 square miles), which means that groundwater aquifers will be less able to replenish, watersheds will be more polluted and the probability of flooding will be greater. Meanwhile, many urban areas and inner-ring suburbs will likely be more distressed than they are today, with a depressed housing market and an increasingly concentrated share of the state’s low- and moderate-income households.

This is not a worst-case scenario. All we need for this picture to become a reality is to keep the land-use policies we have today. In fact, the situation could get much worse if recent proposals for weakening the Pinelands Comprehensive Management Plan, the Highland Regional Master Plan and other long-standing environmental protections are implemented, thereby unleashing sprawling growth into sensitive environmental areas.

Scenario Two: Sustainable Land Management Policy

Scenario two looks to a number of positive shifts on the horizon of state land-use policy that would result in a significantly different socioeconomic/environmental landscape for New Jersey in the year 2021. In this scenario, the same amount of economic growth will occur, but land use will follow a very different pattern.

In scenario two, rural and environmentally sensitive areas will remain far more intact than in scenario one. The management of these resources will be approached more comprehensively, using computer modeling to better identify and evaluate the consequences of any development decision before large sums of capital are invested and permits are granted. Where properties are identified that would cause significant impacts if developed, Transfer of Development Rights (TDR)—a policy tool employed extensively by the state in the Pinelands—will be used as an economic means to compensate owners for preservation without public expenditure.

In scenario two, development that achieves meaningful and measurable performance standards in sustainability—as rated in the U.S. Green Building Council’s LEED for Neighborhood Development—could be encouraged through fast-tracking of proposals that achieve gold or platinum scores in the LEED rating system. The amount of impervious increase (and subsequent water-quality impact) would be minimized through what we envision as an Impervious Cap and Trade form of TDR. Forward-thinking open-space protection programs will ensure that wildlife habitats and corridors will remain as intact as they are today and potentially even be improved through restoration initiatives.

Cities and older towns will become rejuvenated in scenario two as policies shift from favoring development on rural open spaces to redevelopment of previously developed land. An example is the Rowan Boulevard project in Glassboro, where a blighted area within a struggling town was developed into a new, walkable Main Street town center that has attracted major retailers, new residents and offices. Scenario two will see this kind of recycled redevelopment repeated throughout the state, creating desirable town-based communities and lessening the pressure for additional cookie-cutter subdivision tracts haphazardly dispersed in rural areas.

In scenario two a significant amount of development and redevelopment will occur near existing or planned public transportation. Development patterns will employ the best practices of new urbanist design to create desirable communities and a sense of place, with streets that are designed to be safe and inviting for pedestrians and bicyclists. This will be accomplished through the state’s existing Transit Village initiative and the national Complete Streets movement.

The focus on redevelopment and sustainable growth will allow a better mix of housing stock in these revitalizing communities so that lower-income young adults as well as retirees can afford to be in the same neighborhoods as the wealthier middle-class households from which they originate. The landscape and quality of life in New Jersey’s communities will be improved, as will the ecological and economic integrity of New Jersey’s rural land base. Scenario two will be a New Jersey that has the vast majority of growth occurring within Smart Growth areas of the existing New Jersey State Plan. In this scenario, more people will have the option to walk, bike and take public transit—producing a significantly smaller carbon footprint than we have in 2011.

What we are likely to get in 2021 will be a landscape somewhere in the middle of the two scenarios. While inertia would steer us toward scenario one, there is evidence of countervailing trends, with increasing numbers of housing permits going to urban redevelopment projects spurred by the desire of young and older adults to live in vibrant urban locales.

Scenario two is not utopian; the policy tools needed to shift toward this scenario are already available or in the process of being developed. With continued imagination, hard work and dedication, New Jersey could arrive at a landscape ten years from now that is much closer to the sustainable vision of scenario two than the reality of recent decades of sprawling land use and loss of open space.

John Hasse is associate professor of geography and director of environmental studies at Rowan University. Richard G. Lathrop is a professor at Rutgers University and director of the Grant F. Walton Center for Remote Sensing and Spatial Analysis. The full report referenced in this article can be downloaded at gis.rowan.edu/projects/luc.